A glass artwork made by members of the congregation, a liturgical centre conceived together with a workgroup, the open gathering place that was a clear priority for the community during discussions about possible design variations: knowing the story behind the renovation of the church building De Vaste Burcht in Gouda, you can see the engagement of the community in the result. Over the course of the project, this involvement ranged from informing and voting to designing and demolishing together. The renovation of the Vaste Burcht illustrates that co-creation is a carefully weighed combination of different forms of participation. To design with users, you also must be able to design for them and vice versa.

Renovating the church building in Gouda required a significant contribution from community members, both in time and financial support. And that happened. The final design was approved with 95% of the community vote and the necessary resources were gathered. The support was also visible in the collective effort of the church. Congregation members helped with demolition and painting walls and contributed to designs for specific spaces. They also worked together with a glass artist to install coloured glass in the windows of the congregation hall.

This involvement is fantastic, but not always guaranteed. The design process created by Open Kaart is a tool to include users in a project in a constructive and positive manner. The process makes shared priorities and qualities explicit and draws on individual’s expertise to come to an optimal and widely supported result.

Returning to the experience and values of users: in conversation with members of the congregation

Before Open Kaart came into the picture, earlier plans had stalled for lack of broad support within the church community. There was a nice sketch, but no one asked what kind of community the church members wanted to create. An important first question was: how do the church members experience their building and where do they see value in it?

Many have married, baptised their children, or said farewell to loved ones in this church building. A meaningful place to be sure but one with a dated appearance and limited functionality. Through conversations with different groups within the church community, we mapped out how members view the building; what do they appreciate, what can be improved and how do they see their church in the future. This provided input for the design but was also essential in securing approval from the community to begin the renovation.

Making space for a collective perspective

The different perspectives on the church building became input for three schematic designs. To arrive at these schematic designs, familiar reference points had to be triggered. This meant that the conversation turned to design solutions that people could see working and that in turn created space for dialog about prospective qualities of the design. What else is possible? Why is that suitable, or not? An excursion to other new or renovated churches provided additional inspiration.

This process allowed for the formation of a new, shared principal. A new perspective that encompasses and transcends different ideas and solutions. Familiar, something with which people could identify; but also inspiring because it is distinct from the individual suggestions proposed at the beginning of the project. This reframing process provides – contrary to what is often assumed with co-creation – ample design space for the architect. Searching for this space to design openly with an over-arching, unified story is, in fact, essential for a design backed by the users.

Making use of expertise, commitment, and enthusiasm

The involvement of the community members was a continuous, collective effort. Where one person enthusiastically grabbed a hammer for demolition, the other sat down with us to think about the design or offered to help with the financial aspects. Go-getters, silent powerhouses, creative types, attentive thinkers, enthusiastic workers; community members took on the role that fit with their personal strengths. Open Kaart gave a framework to these contributors and fine-tuned the conditions where necessary to let them add to the process and to the quality of the results.

Designing with and for users

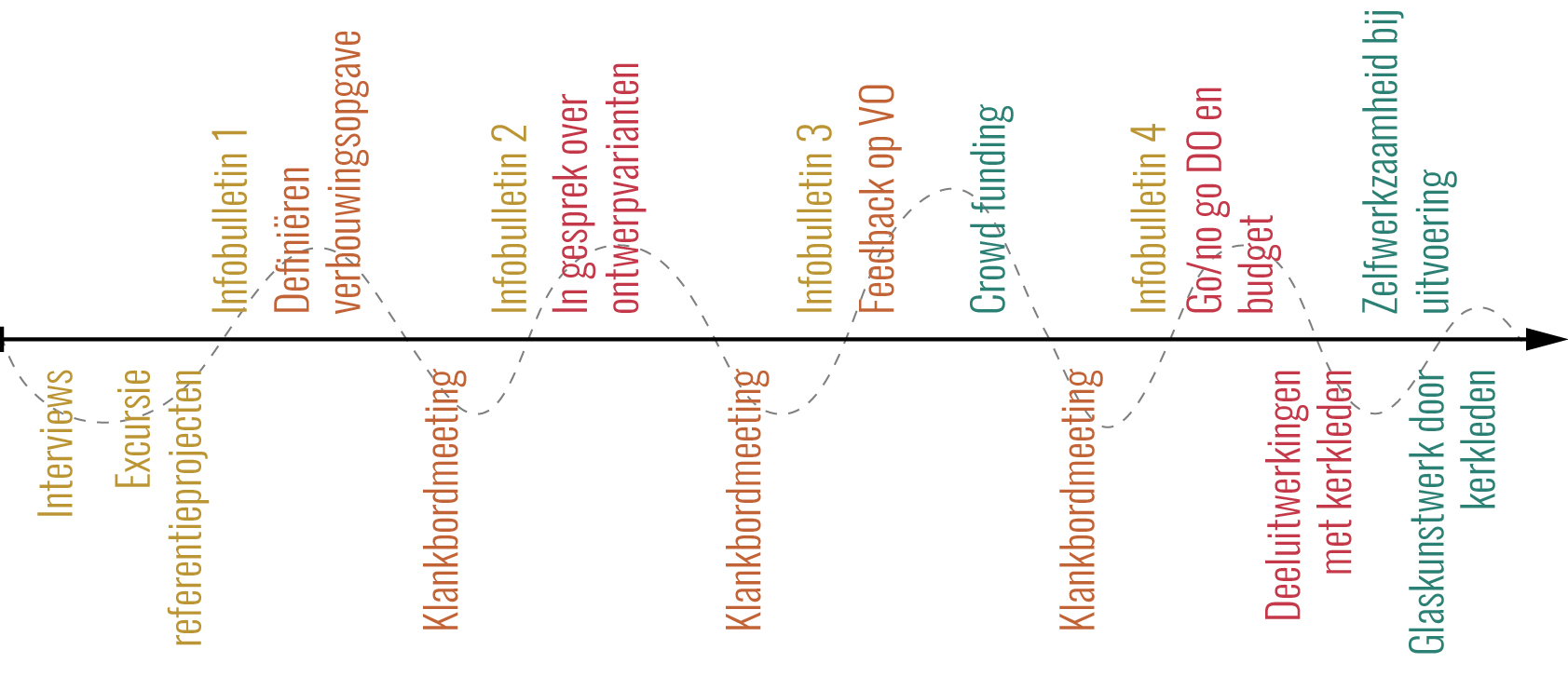

From the first conversation to the grand opening, the interactions with the church community each had a different spin. In the early phases, the church members with largely experts in use and function through their (collective) experiences. For the designers, the art lies in forming a good picture of the church and its members through research. Feedback on design ideas and concept development was used to check if the interpretations of users’ perceptions and wishes matched with the community’s real experiences and needs.

At other times, the church members were more directly involved in the thinking and designing processes. They actively contributed ideas for the design or came together at the drawing table to brainstorm about aspects of the implementation. Alongside the design process, community members also took on critical roles to bring about the renovation, such as organising a crowdfunding campaign and rearranging the outdoor space around the church.

Collective and allocated tasks

Each interaction with the church community had its own colour and flavour, from the first conversation to the grand opening. Members of the church provided complementary knowledge and with demolition, painting and organising the budget they carried out tasks that complemented the knowledge and work brought by Open Kaart as designers. On the other hand, there were forms of interaction where the focus was integration of knowledge, perspectives, and ideas: to come to a new collective foundation for design choices and decisions. As a result, the conversation about the three schematic design options centred on which qualities and values would form the guiding principles for the renewed church building. Different groups worked on different aspects of the design, for example the liturgical centre and new church logo that the community and Open Kaart designed together.

Each interaction with the church community had its own colour and flavour, from the first conversation to the grand opening. Complementary in individually allocated tasks or more focussed on integration of knowledge and different perspectives; researching to form an accurate picture of the church and its members or directly collaborating with ideas and designs.

Combination forms co-creation

To give form to this rich collaboration, it was necessary to not only design with people, but also for them. This resulted in a process where not every interaction would technically be labelled as co-creation. For example, some of the meetings were largely informative. This information was, however, important in having a well-informed discussion about design choices. But there were also limits on how much of a say the church members had in the design decisions. The earlier mentioned schematic designs didn’t provide an endless list of possibilities. Open Kaart proposed rotating the orientation (of chairs in) the congregation hall and adding a hallway along the different rooms, both of which appeared in all three design options. The variations did, however, show that there really were choices within the design and what the consequences of those choices would be for the quality and use of the space and for the budget. Illustrating the different options meant that a concrete conversation could be had with members of the church over these choices.

In this way, each form of participation had its place and function within the project. Collectively they formed a co-creative process with the church community as an engaged partner.

Co-creation: a craftmanship

The assertion that a project cannot reach a suitable conclusion without the engagement of users is not, in and of itself, a guarantee of success. Gathering available energy and directing it into added value for a project requires insight in collaboration, collective decision making and collection of relevant input. It entails constant and careful weighing of what users bring to the table, what the value of this input is, and which form of interaction is required. Insight is needed to ask the right questions and offer the necessary information and tools, but also leadership to choose which input contributes to the quality of the project and which is no longer beneficial.

Co-creation blooms in the relationship between different forms of interaction with users. A design process also needs to be well designed.

With the renovation of the Vaste Burcht in Gouda, this meant that a revitalised church building could be realised with modest means. A place where church members, even before the opening, felt a sense of ownership and found new inspiration.