Zoning requirements demand ‘participation’ when developing an area. But how can this demand be upgraded from ‘standard requirement’ to ‘meaningful contribution’?

Hanneke and Pieter wrote this article at the invitation of gebiedsontwikkeling.nu

Area and spatial development are becoming increasingly collaborative, also with non-professional parties such as residents and local interests. The added value of this engagement is, however, not necessarily self-evident. Half-baked forms of participation frequently lead to a missed opportunity in collaboration with residents and other local parties. Or worse: they contribute to frustration and growing resistance to development.

Expertise about co-creation is, therefore, indispensable in area development. When all the pieces of the puzzle fall into place – participation, design and decision making – the process runs like clockwork, natural and precise. A thoughtful process design makes this cooperation with an added value possible.

Bringing Residents to the Table

More and more tasks and challenges are coming together in area development. Development must be green, circular, energy-neutral, climate-adaptive, nature-inclusive, healthy, and care-neutral. The convergence of these types of projects requires more intensive forms of cooperation between (local) governments, developers, designers and ever more experts and advisors. And, that’s right, something also has to happen with residents and other local interests.

The new zoning laws, which take effect in January 2021, make ‘participation’ a mandatory part of area development. Participation is described by lawmakers as “the involvement of stakeholders early in the process.” Some stakeholders – such as developers and local governments – have an obvious seat at the table. The intention with participation, then, is engagement with the less self-evident partners, such as residents, local entrepreneurs, and resident’s organisations.

“Certainly, within inter-city development with its disparate property ownership, the outcome of development projects is never the result of just one party deciding the future of an area.”

This undoubtedly makes area development more complex, but it is also increasingly becoming a condition for successful results. Certainly, within inter-city development with its disparate property ownership, the outcome of development projects is never the result of just one party deciding the future of an area. Collective decisions must be made which, in turn must be translated into plans and designs with which everyone can identify. Collaboration, specifically with residents and local parties, is then essential.

Unnecessary Embellishment?

The question becomes how you bring about this synergy. The new zoning laws requires participation, largely through an obligation to state reasons to obtain a permit. This means that initiators must credibly demonstrate that local interests are properly involved in the process. Zoning laws do not, however, describe what this involvement should look like. That leaves, to put it positively, space for specifically tailored engagement. The flip side is that there is no established course for a meaningful co-creative collaboration process.

Implementation of this collaborative synergy can, therefore, go awry. Not necessarily through a lack of involvement, but because of an ineffective approach to that involvement. Sometime this is because participation is viewed as a ‘must’ to be checked off easily. Sometimes it comes from a more-for-less attitude; a chance to achieve the same ends for less by transferring responsibility to civilians. And sometimes it stems from an ideology and good intentions, participation as a form of democratisation or charity. These approaches all have a certain naivety with insufficient attention for the complexity of co-creation.

Participation devolves in this way to a disappointing panacea, unnecessary embellishment, or paper-thin window dressing. The result: wasted time, money and energy on processes that are neither useful nor efficient. Or, even worse, that lead to increased frustration, opposition and distance between the different parties involved.

Co-creating with Added Benefits

Enough reasons not to get your hands dirty, so it seems. But here we run the risk of throwing the baby out with the bath water whereby the actual benefit of collaboration remains untapped. Effective collaboration can contribute specifically to a higher quality over-all, something which benefits all parties involved. Additionally, the perception of quality is also higher. A process where those involved feel their voice is heard and taken seriously leads to more satisfaction with the result.

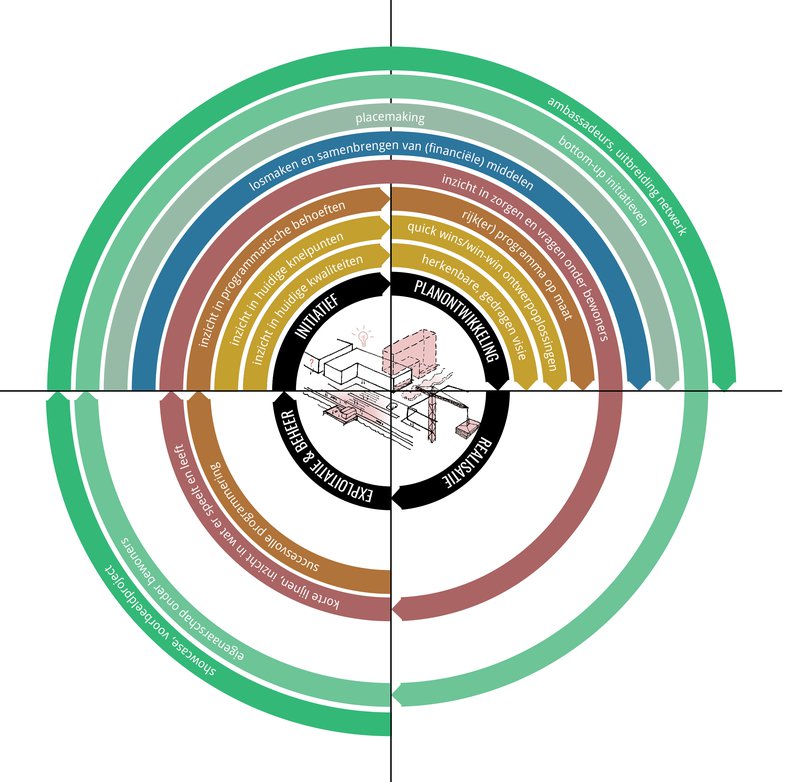

This potential added value of co-creation, for plan and process, comes in many forms from initiative to utilisation (see diagram, NL).

Colour and Flavour

In initial phases, local parties contribute knowledge that simply isn’t on the radar of developers and officials since it is not their everyday living and working environment. This knowledge encompasses information about the physical living environment, but also peoples’ experience of it.

An example of this is the approach ‘programma van wensen,’ an alternative design brief for large scale outdoor projects in the city of Rotterdam. Read more about it (in Dutch) on our expertise page klimaat en straat.

Properly implemented co-creation generates social, political, and financial capital and builds relationships during preparation and realisation of the development enterprise. Think of gathering financial resources, creating ambassadors for the project, new contacts and local initiatives that bring colour and flavour to the development.

These forms of engagement contribute to a sense of ownership that continues to bloom after the realisation of the development project. Those involved feel responsible for (their portion of) the area and care for it.

In our project Polder Nijbroek exploring perspectives for the future together with the local community resulted in a widely supported vision. A vision on a single A4, to be shared among friends and family at the kitchen table. Residents founded a local cooperative with private investment to purchase and develop a vacant farmhouse with 7 hectares of land. Involving residents meant that both time and energy were eagerly invested in the project.

Interplay of Interactions

Each added benefit has, however, its own conditions for success. Gaining insight into the positive qualities and the hurdles in the beginning phases of a project asks a different from of interaction than the stimulation of residents’ initiatives or the gathering of resources. Sustainable area development does not happen by cleverly working around residents and other local interests and then expecting them to make the development successful. It is only possible to make deliberate choices about essential conversations for a project when you have a clear idea of which input you expect from engaging with local parties. These are choices about which conversations to have, who brings what to the table, at what scale the issues must be addressed and which forms of interaction are suitable.

“It is only possible to make deliberate choices about essential conversations within a project when you have a clear idea of which input you expect from engaging with local parties.”

Make the added benefit of co-creation for the development concrete and fine-tune your approach based on it; effective co-creation demands a good process design. The added value of the collaboration becomes apparent throughout the development in the interplay of interactions, the building up of support, trust, enthusiasm and engagement and a high-quality plan.

Designing with Uncertainties

It is critical that designing and participation be parallel processes, to be able to utilize concrete input in conversations about more abstract matters – and vice versa. A good process design makes explicit who has what influence and creates the right conditions for all those involved. It takes the experience of (local) stakeholders as a baseline, makes space to discuss dilemmas (even if the answers aren’t yet clear) and shows how the input gathered from stakeholders is translated in the planning. By presenting design variations early in the process, you quickly make the playing field, conditions, and consequences of design choices comprehensible.

If all goes well, then an effective collaboration leads to added value for the area in development. So, if you ‘have to do something with participation’ anyway, turn the requirement into a blessing by cashing in on the added value of it. Don’t see co-creation as a favour or a ‘must’, but as an opportunity for successful area development.